Titles like James and the Giant Peach (1961), Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964, 1973 & 1998 – more on that shortly), The BFG (1982), The Witches (1983) and Matilda (1988) immediately establish a legendary status for Roal Dahl, but why controversial? Well, we could look at his history as a British spy in the United States, but instead let us look at the often overlooked dimension of race in his most famous work, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

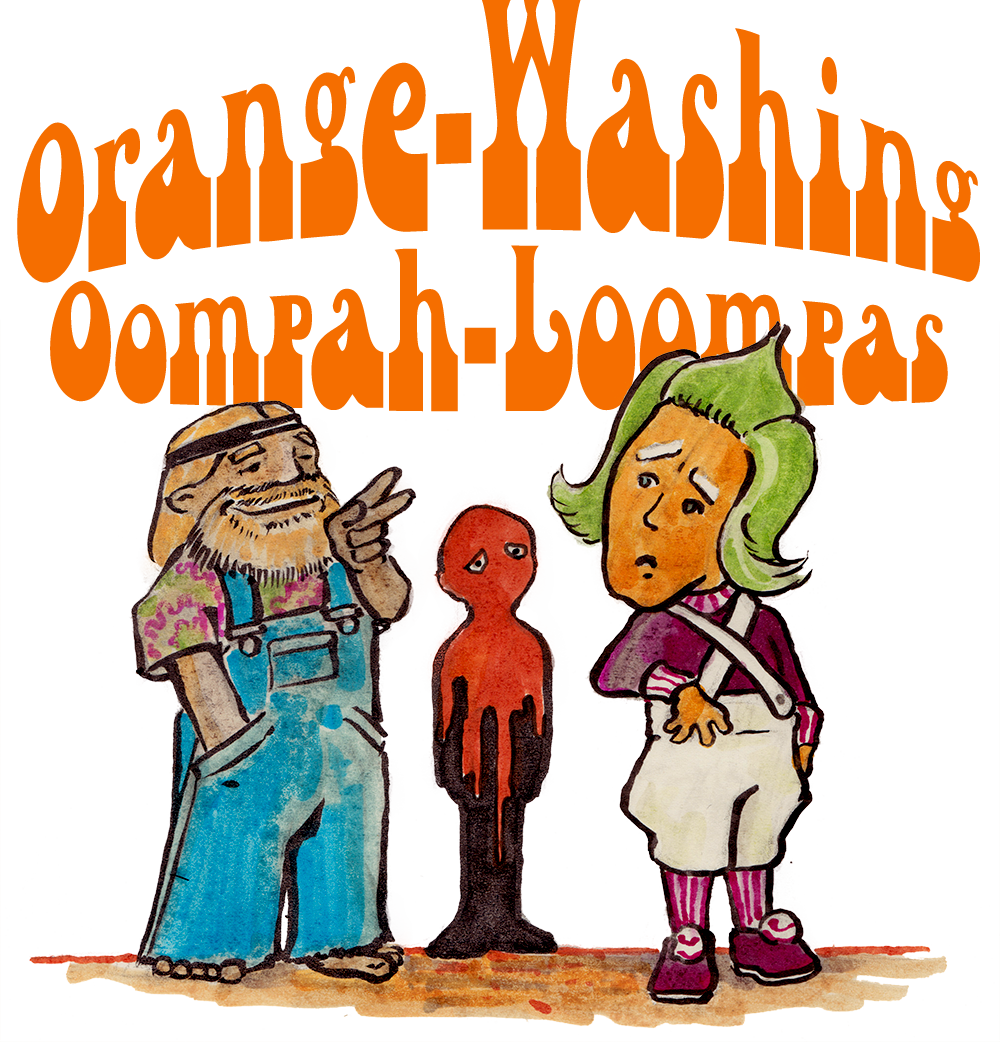

In his 1964 book Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Roald Dahl depicts the iconic Oompa-Loompas as African Pygmies. Yet, in 1971 Mel Stuart’s film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory the Oompa- Loompas are portrayed as little orange people with green hair. But in the 1973 revision of this text Oompa-Loompas are depicted as white, dwarfish hippies. Finally, in the 2005 movie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory Tim Burton portrays the Oompa-Loompas as little brown skinned people; all of whom look exactly the same.

Putting aside Burton’s tendency for problematic casting choices, these three versions of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory (1964, 1973, 1998) mark a Bowdlerization of a work that doesn’t quite address the problem created. Looking back on the 1964 depiction of Oompa-Loompas, the problem is clear; Willy Wonka has brought over from Africa half-naked Pygmies for enforced servitude. According to Jeremy Treglown’s Roald Dahl: A Biography “In the version first published, [the Oompa-Loompas were] a tribe of 3,000 amiable black pygmies who have been imported by Mr. Willy Wonka from ‘the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle where no white man had been before.’ Mr. Wonka keeps them in the factory, where they have replaced the sacked white workers. Wonka’s little slaves are delighted with their new circumstances, and particularly with their diet of chocolate. Before they lived on green caterpillars, beetles, eucalyptus leaves, ‘and the bark of the bong-bong tree.’”

It’s telling that the book went through several iterations, seeking to fix that problem; and still results in labor relations to make Jeff Bezos green with envy. Come 1973, to accompany its new sequel, Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator, a revised edition of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was published, in which the Oompa-Loompas are no longer Pygmies, instead they’re from Loompaland. Illustrator Joseph Schindelman changed their ethnicity modeling them as a fusion of a Lord of the Rings influenced dwarf a post-60’s hippy. In so much as either are considered human there remains a problem of being imported from another country by a person of European descent. No longer of African descent, does the additional motivations of having gladly accepted their new lot as wage-free-workers do any work to soften the colonialist practices of this chocolate factory?

Apparently it was in this edition where “hornswogglers and snozzwangers and those terrible wicked whangdoodles” were created as a reason for their desire to leave that “thick jungles infested by the most dangerous beasts in the entire world,” after how many generations? Would a Willy Wonka be able to make such a determination? Or does it continue to read as post-hoc rationalization? It certainly would elevate his status as a big-game hunter if these creatures were so genocidal.

There may be an argument to be made that Dahl was actively satirizing the practices of the chocolate industry of the time. Dahl must have at least been aware that the cacao plantation workers in Ivory Coast, the biggest producer of chocolate, were practically enslaved African children. Whether that truly bothered the Englishman remains debated. When the NAACP protected the book’s publication Dahl insisted there was no racist intent behind the Oompa Loompas but claimed to sympathize enough to rewrite them in time for the second US edition. A look at the Brittish editions makes that claim all the more dubious as that version’s art would not see a change for a number of years later.

Since the book functioned as a twisted morality play; a whimsical fantasy juxtaposed by grotesque and sometimes harshly violent comedic scenarios, it’s difficult to gauge if, or how much consideration was offered the plight of these laborers. As a child it was easy to enjoy the dark fate of one of those terrible children but that seemed to be part of the problem, at least according to author Eleanor Cameron. In October of 1972 The Horn Book magazine published the first of a three part essay titled “McLuhan, Youth, and Literature” by Eleanor Cameron. In it, the author labeled Charlie and the Chocolate Factory “one of the most tasteless books ever written for children,” finding it to be “sadistic” and “phony.” This incited a series of back and fourth letter-to-the editor type replies from Dahl, the first of which was published in the February 1973 issue of Horn Book.

MRS. ELEANOR CAMERON (I had not heard of her until now) has made some extraordinarily vicious comments upon my book Charlie and The Chocolate Factory (Knopf) in the October issue of this magazine. That does not worry me at all. She is free to criticize the book itself for all she is worth, but I do object strongly when she oversteps the rules of literary criticism and starts insinuating nasty things about me personally and about the school teachers of America.

Roald Dahl: From the February 1973 issue of The Horn Book magazine

October 2006 Faber and Faber. ISBN: 0-307-39491-3

Failing to meet his deadline for submitting a screenplay adaptation for the 1971 film, Dahl would later disowned it. He would say he was “disappointed” because “he thought it placed too much emphasis on Willy Wonka and not enough on Charlie.” In other instances he would complain about the ghost-writers David Seltzer and Robert Kaufman, for the philosophical maxims given to Wonka. There’s little to be found regarding Dahl’s opinion of orange Oompa-Loompas but on the topic of race and the movie’s title, Dahl and the producers remained at odds. During the 1960s, the term “Mister Charlie” had been used as a pejorative expression in the African-American community for a “white man in power” (historically plantation slave owners) and press reports claimed the change was due to “pressure from black groups”. Charlie was also known to be a euphemism for cocaine, but it’s doubtful either of those details mattered to Cameron who was focused primarily on Dahl’s book.

In her 1972 article, Cameron decried the Oompa-Loompas, who were portrayed as abused, half-naked, African pygmy slaves. The debate continued as to whether the 1973 change of the Oompa-Loompas was a direct result of Cameron’s criticism. Some would say it’s more likely that the changes had already been put in motion by the time her article “McLuhan, Youth, and Literature” was published, but the narrative around these choices in representation remain as chewy as an ever-lasting-gob-stopper. As recently as September 13 2017 The Guardian wrote “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory hero ‘was originally black'” in which wife and movie producer Liccy Dahl said: “His first Charlie that he wrote about was a little black boy.”

October 2006 Faber and Faber. ISBN: 0-307-39491-3

Born in Canada, March 23, 1912 one may think her exposure to radical though may have began some six to ten years later when she found herself in Berkeley Califonia. Studing at UCLA and the Art Center School of Los Angeles, she joined the Los Angeles Public Library in 1930 before launching a successful writing career of her own with the 1954 publication of The Wonderful Flight to the Mushroom Planet. She would also write two books of criticism and reflection on children’s literature, the first was The Green and Burning Tree, in 1969 which led to the rising which empowered her to take on the widely popular Dahl. Below you can read some of what she had to say about him.

“Now, there are those who consider Charlie to be a satire and believe that Willy Wonka and the children are satiric portraits as in a cautionary tale. I am perfectly willing to admit that possibly Dahl wrote it as such: a book on two levels, one for adults and one for children. However, he chose to publish Charlie as a children’s book, knowing quite well that children would react to one level only (if there are two), the level of pure story. Being literarily unsophisticated, children can react only to this level; and as I am talking about children’s books, it is this level I am about to explore.

Why does Charlie continually remind me of what is most specious in McLuhan’s world of the production and the stunt? The book is like candy (the chief excitement and lure of Charlie) in that it is delectable and soothing while we are undergoing the brief sensory pleasure it affords but leaves us poorly nourished with our taste dulled for better fare. I think it will be admitted of the average TV show that goes on from week to week that there is no time, either from the point of view of production or the time allowed for showing, to work deeply at meaning or characterization. All interest depends upon the constant, unremitting excitement of the turns of plot. And if character or likelihood of action — that is, inevitability — must be wrenched to fit the necessities of plot, there is no time to be concerned about this either by the director or by the audience. Nor will the tuned-in, turned-on, keyed-up television watcher give the superficial quality of the show so much as a second thought. He has been temporarily amused; what is there to complain about? And like all those nursing at the electronic bosom in McLuhan’s global village (as he likes to call it), so everybody in Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory is enclosed in its intoxicating confines forever: all the workers, including the little Oompa-Loompas brought over from Africa and, by the end of the book, Charlie and his entire family.To McLuhan, as Harold Rosenburg has pointed out, man appears to be a device employed by the television industry in its self-development. Just so does Charlie seem to be employed by his creator in a situation of phony poverty simply a device to make more excruciatingly tantalizing the heavenly vision of being able to live eternally fed upon chocolate. This is Charlie’s sole character and being. And just as in the average TV show, the protagonists of the book are types, extreme types: vile nasty children who are ground up in the factory machinery because they’re baddies, and pathetic Charlie and his family, eternally yearning and poor and good. As for Willy Wonka himself, he is the perfect type of TV showman with his gags and screeching. The exclamation mark is the extent of his individuality.

But let us go a little deeper. Just as McLuhan preaches the medium as being the message — the sensory turn-on — so Charlie and the Chocolate Factory gives us the ideal world as one in which a child would be forever concerned with candy and its manufacture, with the chance to live in it and on it and by it. And just as McLuhan seems to have lost sight of the individual and his preferences and uniquenesses, so Willy Wonka cares nothing for individual preferences in his enthusiasm for his own kind of global village. Just as McLuhan puts before us the question of leapfrogging Indonesia into whatever age we think best for it, so the question is asked why Mr. Wonka doesn’t use the little African Oompa-Loompas instead of squirrels to complete certain of his processes. Brought directly from Africa, the Oompa-Loompas have never been given the opportunity of any life outside of the chocolate factory, so that it never occurs to them to protest the possibility of being used like squirrels. And at the end of the book we find the bedridden grandparents being snatched up in their beds and, though they say that they refuse to go and that they would rather die than go, they are crashed through the ruins of their house, willy-nilly, and swung over into the chocolate factory to live there for the rest of their lives whether they want to or not.

What I object to in Charlie is its phony presentation of poverty and its phony humor, which is based on punishment with overtones of sadism; its hypocrisy which is epitomized in its moral stuck like a marshmallow in a lump of fudge — that TV is horrible and hateful and time-wasting and that children should read good books instead, when in fact the book itself is like nothing so much as one of the more specious television shows. It reminds me of Cecil B. De Mille’s Biblical spectaculars, with plenty of blood and orgies and tortures to titillate the masses, while a prophet, for the sake of the religious section of the audience, stands on the edge of the crowd crying, “In the name of the Lord, thou shalt sin no more!”

If I ask myself whether children are harmed by reading Charlie or having it read to them, I can only say I don’t know (3). Its influence would be subtle underneath the catering. Those adults who are either amused by the book or are positively devoted to it on the children’s level probably call it a modern fairy tale. Possibly its tastelessness, including the ugliness of the illustrations, is, indeed (whether the author meant it so or not), a comment upon our age and the quality of much of our entertainment. What bothers me about it, aside from its tone, is the using of the Oompa-Loompas, and the final indifference to the wishes of the grandparents. Many adults see all this as humorous and delightful, and I am aware that most children, when they’re young, aren’t particularly aware of sadism as such, or see it differently from the way an adult sees it and so call Charlie “a funny book.”

Eleanor Cameron October 1972 issue of The Horn Book Magazine

Discover more from

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.